DAWNING

Interview by

Svetlana Bachevanova

DAWNING is a mission-driven, non-partisan organization that combines the rigor of the social sciences with the power of the visual arts. Its work crosses disciplines and borders to generate new knowledge from the lived experiences of people at the center of urgent issues. The organization’s mission is to pursue the truth about social and environmental challenges in forgotten corners of the globe, to understand them collaboratively with those who live them, and to share them through narratives in which the protagonists feel dignified and comfortable. DAWNING envisions a world where these voices influence policy and shape public dialogue on the global stage.

Cover photograph: Nick Parisse; Watercolor portrait includes: Eric Andriantsialonina, Raul Roman, Nick Parisse and Rafe H. Andrews during fieldwork in Kenya. Watercolor and ink on paper: Eric Andriantsialonina

How does Dawning identify and choose the issues you address, and why Pipe Dreams about water in Kenya?

Raul Roman: We are interested in every aspect of the human experience. Our first seven projects were the product of crowdfunding: we chose exactly what we wanted to do, focusing on issues such as immigration, the impact of climate and environmental challenges on humans, human trafficking, the impacts of war, documenting different forms of injustice across Africa, Asia and Latin America. In 2018, DAWNING started getting hired by international organizations to apply our methods in areas where there was mutual interest –and we learned a lot from those experiences. In 2024, DAWNING started designing multi-year global research agendas that we’re starting to implement with the help of donors and foundations. So, there is not only one way for us to identify the issues we choose to address at DAWNING.

Why water scarcity in Kenya? We were having conversations with Water.org in the summer of 2021, in the middle of the pandemic, and they asked for a formal proposal to do something in Africa related to water. After several iterations we presented the design for Pipe Dreams: an ambitious deep dive into how water scarcity impacts the rights of women and girls in Kenya. We were hungry to return to the field after months and months of pandemic anxiety. Water.org provided the funds, and two months later our team was in the field.

Rafe H Andrews: There was a real ethos of preparation-meets-luck for this project. We knew we were seeking unexpected links between climate change and women’s rights and I think even before heading to Kenya we had a strong conviction based on our research that we were onto something – a kind of balloon-chase that was sure to be revealing and take us down unexpected roads, which is always the goal. We were met by the great luck of being able to work at all during the pandemic years, when so many organizations were totally grounded. So we went in prepared and with a lot of gratitude. The “why does this matter”, like with any good project, was answered by the people we met along the way – sometimes in the form of answers, sometimes in the form of more questions.

Photo: Rafe H Andrews

Long'ech. Turkana

How did you prepare for this extensive research? And assemble the team?

Raul Roman: We didn’t have much time to prepare, but by then we had a lot of experience and know-how. As project director, I had dozens of decisions to make. The first was to bring the core team together. Nick and Rafe were already on board, but we still needed a research lead (Camille Sachs) and a fieldwork logistics manager (Edinah Samuel). Once they joined, Camille and I worked with Edinah to finalize an intense three-week schedule covering more than 20 locations across five regions. Camille focused on the literature review while I stayed with Edinah on the logistics — security, permits, transport, accommodation — and recruited ten research assistants and translators plus four drivers. I also met regularly with Nick and Rafe to shape the project’s photography vision.

Still, something was missing. I couldn’t name it yet, but two weeks before departure I felt it like a jolt — this project needed a graphic novelist. It made no rational sense; it was pure instinct, like a palpitation I couldn’t ignore. We’d worked with Eric years earlier on our Niger project, where he created powerful explanatory illustrations. I’d kept in touch, hoping for another chance to collaborate. I emailed him and asked to meet immediately. Minutes later, we were face-to-face on Zoom. I hadn’t planned my pitch and hadn’t mentioned it to anyone on the team. But the moment I saw his face, I knew. I went straight to the point: “Can you join us in Kenya in two weeks?”

Eric Andriantsialonina: When Raul asked me to come along, I was terrified and excited at the same time, but my intuition told me to go. At first, we didn't know exactly how I would contribute, but I was confident that my years of experience in comics and sketching would be an asset in the field. Especially since Raul reassured me that, as it was a team effort, I would have all the interview transcripts and photos at my disposal to do my work.

I then read the literature review that was sent to me and took a sketchbook with me so I could draw on site and collect as many visual elements as possible that would be useful to me later.

Nick Parisse: My pre-fieldwork process is consistent across DAWNING projects. After I digest the literature review, I begin to identify keywords and phrases that I want to translate into a photography vision for the project, in partnership with Rafe and Raul. I become as much as an expert on the issue as possible before fieldwork. I begin by writing out a "wish list” of themes, places, events and people I'd like to see and photograph, and we shape that list in conversation with my colleagues. My next step is to compile inspirational reference imagery to help shape the look and feel of the project.

It’s a very collaborative process which reaches its pinnacle once the team arrives in the field. That’s when the rubber hits the road. Our team is extraordinarily coordinated. We all move together and split for specific tasks through an iterative process. For example, I might have photographed something that needs additional investigation, and I need support from my colleagues to conduct interviews; or someone has conducted an interview that requires shooting portraits and digging deeper for photographic evidence, and I go there.

Rafe H Andrews: My prep was twofold. As a producer I wanted to make sure our team could stay healthy while doing intense work in unknown places during the middle of a global pandemic. We took the proper Covid precautions, but I also wanted people to feel like they were being looked out for on a holistic level – I prepared group workouts, meditations, and kits of vitamins and supplements everyone could access throughout fieldwork.

As a photographer I was really nervous about how to best collaborate in the field with Eric. I’d worked with illustrators, but never this closely. And while a lot of news or nonprofit organizations carry their creative work out in silos with everyone left to complete their own part (photographers can notoriously be lone wolves) that’s not really how we do things, so I was keen on figuring out a workflow in the field that allowed the photos I would take to feed off of what Eric was drawing, and vice versa. We’ve been fortunate to work on many projects together since then and I’m proud to say (as I believe is reflected in the book) that the two disciplines really do speak to each other, each one revealing things that the other cannot.

Photo: DAWNING/Rafe H Andrews

Eric Andriantsialonina, Graphic Storytelling Lead, Camille Sachs, Research Lead, Raul Roman, Project Director, and Adan Kosar, Research Fellow, during an interview on the outskirts of Kalokol, Turkana.

You have a multi-disciplinary approach including narrative, photographic and artistic elements. Why do you use this approach?

Rafe H Andrews: I think it’s because we love jazz. I alluded to this briefly before, that nothing we do is in silos and that our approach is not the way a lot of organizations traditionally conduct this type of work. But the structures that exist for people to conduct research or around the artistic mediums we use are jumping off points, not fixed pathways guaranteeing we’ll be successful. How boring and lonely would that be if we thought we knew everything and didn’t need each other to figure things out along the way? I’ve been around DAWNING since the beginning and always saw the team as a merry band of professional misfits: we know our jobs but also place a high value on mystery as a natural connecting point between the arts and sciences. Despite modern science sometimes carrying a more sterile reputation, the point is discovery. Our approach is to use our tools at the highest technical levels so we can lean into the mysteries of things we don’t fully know about, and riff off of one another in the process. Kind of like jazz.

Raul Roman: The original aim of this approach was simple: to pursue truth with the highest possible credibility. DAWNING is unusual in that it combines the rigor of social science research with the power of the visual arts to generate new knowledge. Blending disciplines and perspectives is essential to creating a richer, deeper, and more trustworthy picture of reality.

And then there is the power of true collaboration. The real magic of discovery happens when people from very different worlds come together to work on something far bigger than themselves.

How did you come to the idea for including graphic novel pieces in your work?

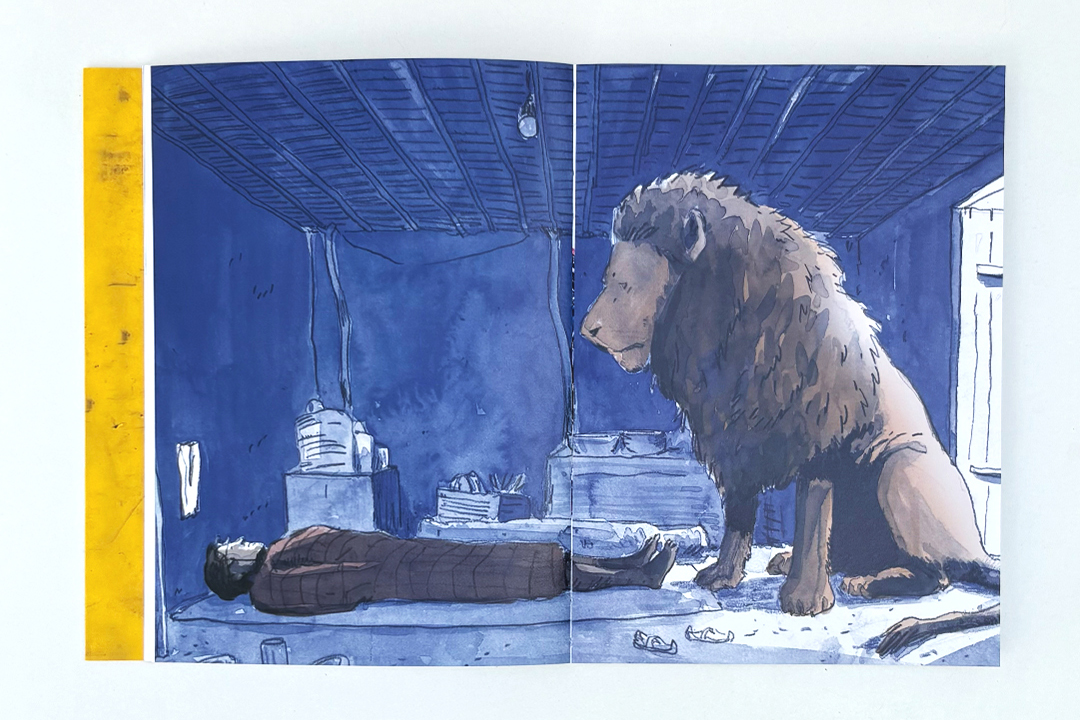

Eric Andriantsialonina: As a comic book author, I can travel through time. I can recreate the past or imagine the future. I can illustrate what people think, bring to life the stories they entrust to us.

And I think that this discipline has its place in this type of complex research. Because it allows us to go where there were no witnesses, where there were no photographers.

And what I found very interesting in what we do is that comics, photography, and text—each of these disciplines is strong on its own, but their combination creates something even stronger.

Raul Roman: The meaning and depth of a graphic novel changes entirely when you place it alongside photographs of the real people who inhabit its pages. And a photograph gains new layers when you’ve first met that person through the intimate narrative of a graphic novel.

You can see this now, as you open Pipe Dreams — but when I invited Eric to join the team, it was only a hunch. It was a leap of faith; we didn’t know how it would work. As Eric said, our first intuition was that photography alone couldn’t capture everything this book needed to convey. Serious violations of women’s rights, like those in these pages, often have no witnesses beyond the victims or survivors themselves. Through graphic storytelling, we could visualize trauma in a way that is accurate, yet also respectful and loving — because drawing someone is, in itself, an act of love.

Graphic novels are a special art form because they ask the reader to participate. And when you discover that the protagonist speaking to you in those panels is a real person, you naturally want to see their photograph. That combination is what brings Pipe Dreams fully to life — speaking to you, one-on-one.

From the book Pipe Dreams

Watercolor: Eric Andriantsialonina.

Most of the illustrations depict situations that are hard to photograph. Were they drawn based on witness accounts? What is the process?

Eric Andriantsialonina: All illustrations are based on the testimonies of the people we talked to –hundreds of pages of interview transcripts. During interviews, when the team feels that the story the person is telling us could potentially become a graphic novel, we collaborate with that person to gather all the visual aspects of the story. At the end of fieldwork, we sort through the stories and choose the ones that can help us anchor each book chapter.

I draw a lot in the field, and I also take my own photos with my phone. This allows me to have better memories of the atmosphere and the colors of a place. Later it will help me to recreate that place, if needed. But of course, Nick and Rafe's fantastic photos help me enormously in my creative process. Every night in the field, I receive a selection of the pictures of the day curated by Nick and Rafe.

The process is as follows. I make a digital storyboard of the novel, which I then show to Raul. Raul reads it, gives me feedback (written or drawn), and then I propose a new storyboard. These exchanges can go on for a while; we call it our ping-pong match. Once we have the final version of the storyboard, I start on the drawings. For Pipe Dreams, the drawings were done in pencil and watercolor –there is no digital work. The big difficulty with direct colors is that if there's a mistake, you have to start all over again. I had to redo two or three panels from scratch in the whole book because some of the colors weren't right.

What is the message of Pipe Dreams and who do you want to reach with the book?

Raul Roman: Pipe Dreams shows why protecting women’s rights must be an urgent policy priority in Kenya — and how the crisis it reveals spans far beyond its borders. At its core, the book is a wake-up call about the global water crisis — something we all depend on, yet far too many of us take for granted.

It’s both a reality check for those in power and a call to action. But above all, Pipe Dreams was made for the very people whose stories it tells. That’s why our priority is to bring it back to Kenya as a public exhibit, where the voices at its heart can speak directly to their communities.

Rafe H Andrews: At the most personal level I have always seen this project as a way of honoring my mother, and, more widely, mother figures everywhere. The level of sacrifice and provision I’ve experienced as a son is so clearly reflected in the struggle of women across Kenya to provide the basic human right that is water access to their children, families, and neighbors. I saw my own mother in all of them. That’s a cool thing that happens the more you do this: you see one’s you’ve loved, and even one’s you’ve lost, in the faces of people you’ve never met. And while we discovered a lot of nuances to that daily quest mothers must make to provide water, for me this book is proudly and unequivocally dedicated to the spirit of motherhood that continues to make the world go ‘round.

Nick Parisse: We want to make people aware of the issues these women and girls face on a daily basis and start discussions on how to influence policy change to improve their situation. We hope Pipe Dreams will become a tool for education and a catalyst for change.

Eric Andriantsialonina: We want people to reflect about their own stories, in their own country, when they read the book. The idea is to make change happen.